MAYAMAN.IRL ( )

Interviewed Mar 2025. Photographed by James Kramer.

Maya Man is a New York City based artist who explores identity and performance online. Her work has been exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Tate Britain, and MOCA Los Angeles. We visited her NYC studio and DIY art space, HEART, which houses her collection of Addison Rae ephemera, 2010s teen magazines, and HEART merch featuring absurd slogans on thongs, “I 🩷 HEART” tees, and her book FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT, filled with unorthodox, generated self-help quotes like “Be Disrespectful to One Another.” The space, filled with pink and pop culture nods, echoes her childhood Bat Mitzvah theme: “Pink and Chocolate” — a concept she still embraces.

TRIPLE3: Jumping a little bit into your practice. How essential is self documentation in the digital age, particularly in relation to one’s online presence?

MAYA MAN: I’ve always felt panicked about forgetting details about myself and my experiences. My relationship to self-documentation is really rooted in memory and trying to understand how the self shifts over time. It’s why I journal, and it’s why I’m drawn to the ways people represent themselves online because identity is fluid, always changing. Being able to look back at something you posted, especially if it’s something you wouldn’t share now, reveals something meaningful about who you were in that moment. I’ve built tools around this, and a lot of my work is driven by that impulse to document, to make sense of an evolving framework for identity that’s always fascinated and haunted me. That’s really the core of it.

3: Could you speak to how your personal interests shape your exploration of femininity, identity, and authenticity in digital spaces?

M: It’s always felt natural. My bat mitzvah theme was pink and chocolate, and honestly, the photos from that period of my life look like my work now. I’ve always been drawn to traditionally “girly” aesthetics, but it took me time to feel ready to make work about that culture. In college, especially studying computer science, I felt pressure to prove I was “serious” or “smart,” which distanced me from my instincts. I worried that if I made work about femininity or aesthetics I loved, especially using code, it wouldn’t be taken seriously, especially by the imaginary male programmer in my head. Eventually, I realized that my real interest was in understanding why I was drawn to certain forms of media, like advertising aimed at girls. Once I let go of needing a tech-bro type of validation, I started making more honest, conceptually driven work. Now, I feel like my practice sits between two worlds: some people come for the code, others for the themes. I like that both can exist together.

Digital Quotes from FAKE IT TILL YOU MAKE IT (2022)

THE MODEL MINORITY IS A MYTH! (2021) Billboard, Courtesy of For Freedoms

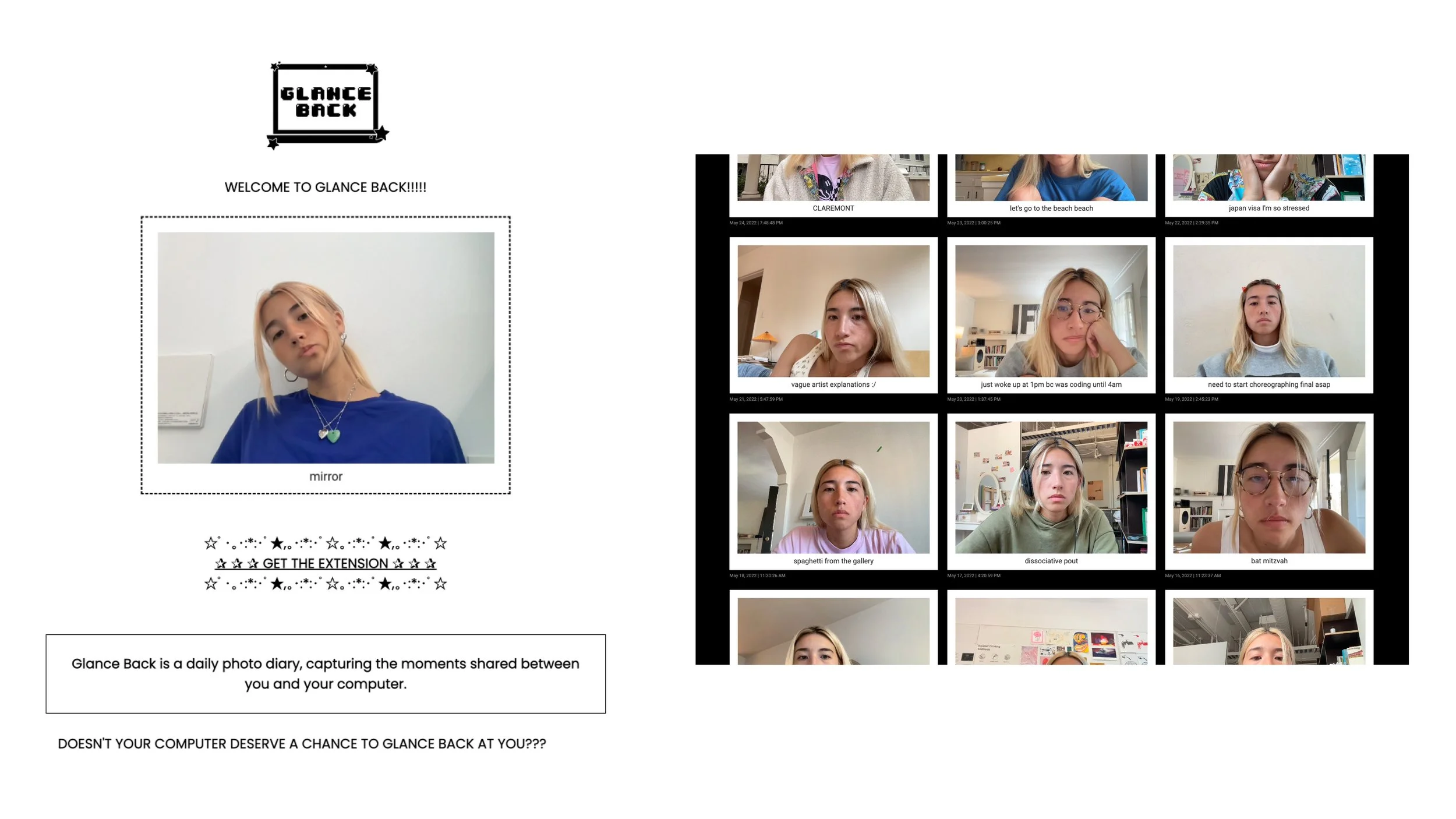

Glance Back, a Google Chrome extension (2018)

3: As someone with a background in dance, how would you contrast the experience of performing in traditional settings with that of performing online?

M: I see a lot of overlap between performing on stage and performing online. Growing up as a competitive dancer, I was used to a quantifiable scoring system being tied to how well I performed. Being on stage and posting online feel really connected to me. Dance conditioned me to constantly analyze how I present myself, especially in the studio, surrounded by mirrors. But one big difference is that in dance, you perform choreography created by someone else, there’s structure and purpose. Online, you have to choreograph yourself, and that lack of direction can feel aimless and harder to navigate.

3: How does your approach to generative art differ from more traditional artistic practices?

M: I’m especially drawn to generative work because of the element of chance it allows. In my software-based pieces, I often build in an element of randomness, so even I, as the artist, don’t know what will happen when the code runs. While I define the structure and parameters, I like relinquishing some control. That unpredictability feels connected to how we encounter things online, through algorithms, luck, or chance. Unlike video, code-based work has no fixed beginning or end; it’s infinite, fluid, and always changing, which really excites me.

3: Could you speak more to your book Fake It Until You Make It and generally the randomness?

M: The book includes the full JavaScript source code. It runs with a random seed each time, which drives all these decisions. Whether it is color palette, layout, background, and even the language. The algorithm is collaging together text: it fills in blanks using phrases I pulled from real Instagram graphics. So if I saw “believe in yourself,” I’d drop “believe in” into a list of verbs, and it might spit out “hate in yourself” or “love in yourself.” It’s not AI, just collage-style randomness and the results can be really absurd but still feel emotionally familiar.

3: Maybe you could speak to your Glance Back project and what that process was like for you. It seems like there was such widespread participation in that.

M: Yeah, Glance Back is really different from my other work because it’s participatory. Most of what I make, you just look at, but this is something people use, and that’s changed how I think about it. It started as a self-documentation tool I wanted for myself, but now it’s on thousands of people’s computers, quietly capturing their lives. That feels really meaningful. I can’t see their photos, they’re private, but I still feel connected to them. It’s become a networked performance, and it’s wild to have made something that people use every day, not just look at once.

3: With Triple, we’ve recently been talking a lot about community and how it has brought people together. Can you speak towards the community around HEART?

M: Yeah, HEART totally changed my life. I’d spent so long going to shows and events that inspired me, but it never felt possible to create those spaces myself. I started HEART because I knew so many artists doing incredible work about the internet and pop culture, and I wanted to give them a space to show and talk about it, especially since the traditional art world doesn’t always make room for that. Starting the space in SoHo was serendipitous, but also a response to feeling isolated in my own practice. I wanted something more connected. It has taught me so much.

Read more about Maya Man in Triple Issue 2